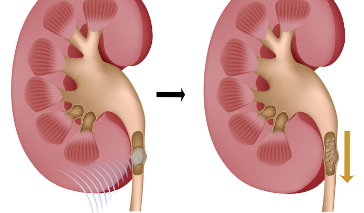

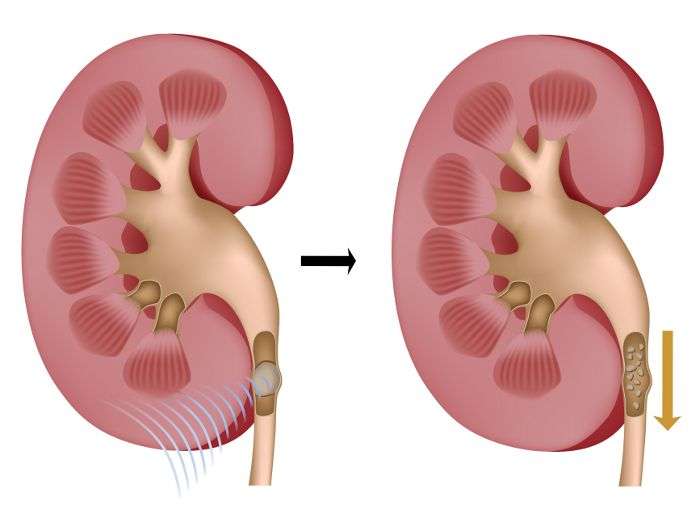

Lithotripsy is a procedure that uses energy (shock wave therapy) to break up kidney stones (calculi), bladder stones, or deposits in the ureter (ureter stones) when they cause complications or are too large to make their way through the urinary tract without intervention.

Roughly 90 percent of calculi can pass out of the body in urine without treatment. But when the stones cause blockage, severe discomfort, pain, frequent urinary tract infections, or bleeding, lithotripsy can help break them up into smaller pieces that can work their way out of the urinary tract.

There are two types of lithotripsy: extracorporeal, when the shock waves are delivered from outside of the body, and intracorporeal, when they're delivered endoscopically.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

Extracorporeal is the most common and widely used form of lithotripsy. During this non-invasive procedure, a fluoroscopic x-ray imaging system or an ultrasound imaging system is first used to pinpoint the stones' location. A water-filled cushion or "coupling device" is either placed on the patient’s abdomen or, more often, under his back at kidney level, then high-energy shock waves – generated outside the body – are directed through the cushion, fragmenting the stones into pieces small enough to pass during urination.

Extracorporeal is the most common and widely used form of lithotripsy. During this non-invasive procedure, a fluoroscopic x-ray imaging system or an ultrasound imaging system is first used to pinpoint the stones' location. A water-filled cushion or "coupling device" is either placed on the patient’s abdomen or, more often, under his back at kidney level, then high-energy shock waves – generated outside the body – are directed through the cushion, fragmenting the stones into pieces small enough to pass during urination.

What to Expect with ESWL

The procedure typically takes between 45 and 60 minutes and can cause some pain, so patients are typically given either local or general anesthesia. Depending on the type of anesthesia used, patients may feel the shock waves, which some liken to a tapping sensation or an elastic band reverberating off of the skin.

Following the ESWL Procedure

After the procedure is over, patients can expect to remain in recovery for up to two hours. Provided there are no complications, many will be able to go home the same day.

Because there is a risk of infection from bacteria released from the stones, it is common for physicians to prescribe a course of antibiotics. Doctors also recommend that people recovering from ESWL drink plenty of water to help lubricate the stones as they pass and lessen discomfort. Following treatment, it is normal to have blood in the urine as well as some abdominal pain.

Patients can also experience extreme cramping as the fragmented stones pass through the urinary tract. This discomfort begins shortly after treatment, can last for four to eight weeks, and can be relieved using over-the-counter painkillers such as naproxen (Aleve) or ibuprofen (Motrin and Advil).

Since the procedure is non-surgical, most patients can get back to their daily physical activities within one to two days, and can return to their regular diets. However, it can take between a week and several weeks for the stones to fully pass.

Is ESWL Right for You?

Though ESWL is widely used, not every patient is an ideal candidate. Those who are not good candidates for the procedure are:

- Pregnant women

- People with infections, skeletal defects, kidney failure, or bleeding disorders

- People who are morbidly obese

- Patients with pacemakers who have not received authorization from their cardiologist

How Well Does ESWL Work?

Success is contingent upon the number of stones, stone size and location, a patient's weight, and the stone’s composition.

Success rates for individual kidney stones are 80 percent when a stone is under 1 cm wide, 60 percent for those between 1 and 2 cm, and 50 percent stones larger than 2 cm.

Depending on stone size and density, they can remain in the affected organ and may require multiple ESWL treatments. In cases where this form of treatment fails, a minimally invasive technique known as intracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy can be conducted.

Intracorporeal Lithotripsy

When stones are unable to be fractured by way of extracorporeal lithotripsy due to position, density, or size, the surgeon may have to take an endoscopic approach. Known as intracorporeal lithotripsy, the procedure is most often performed via ureteroscopy, in which a small, long tube with a light source and camera at its tip is inserted into the urethra and guided up the urinary tract until the stones are located. A variety of instruments can be used to apply energy and break up the calculi:

- Lasers

- Ultrasound shock waves (done endoscopically via an incision in the abdomen)

- Mechanical devices (which act like small jackhammers)

Graspers or a wire basket are then often used to extract the shattered pieces, or are left and allowed to pass out of the urine spontaneously.

Complications of Lithotripsy

While the lithotripsy is typically safe, hematuria (blood in the urine) and edema (swelling in and around the organ) are the most common symptoms. Other complications can include:

- Bleeding around the kidney, which may require a blood transfusion

- Infection of the kidney

- Pieces of the stone blocking urine flow from the kidney. This could cause immense pain or damage to the organ.

- Pieces of stone left in the body that may require future treatments

- Ulcers in the stomach or small intestine

- Kidney failure following the procedure

- Urinary tract infection from bacteria discharged from the stone

- Capillary damage

- Hypertension

Cost of Lithotripsy

The cost of lithotripsy ranges depending on the number of calculi, the type of lithotripsy required, and the size of the stones.

References:

Stone Fragmentation Techniques: Extracorporeal Lithotripsy. (2011). Oxford American Handbook of Urology.

Lithotripsy. (2013). The National Kidney Foundation: A to Z Health Guide.

Kidney Stone Treatment: Shock Wave Lithotripsy. (2013). The National Kidney Foundation: A to Z Health Guide.